It’s been described as “an episode without precedent or parallel in the modern history of the British empire. Not surprisingly, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of April 13, 1919, spawned a wealth of outporuing from Indian writers and poets that author-critic-literary historian Rakshanda Jalil has painstakingly brought together in a seminal volume that will be an eye-opener for the present generation for the lows to which a ruler can stoop.

“While a grat deal of scholarly work has been done on Jalianwala Bagh, it’s reflection in Indian literature in the different bhashas and also in English has been overlooked.

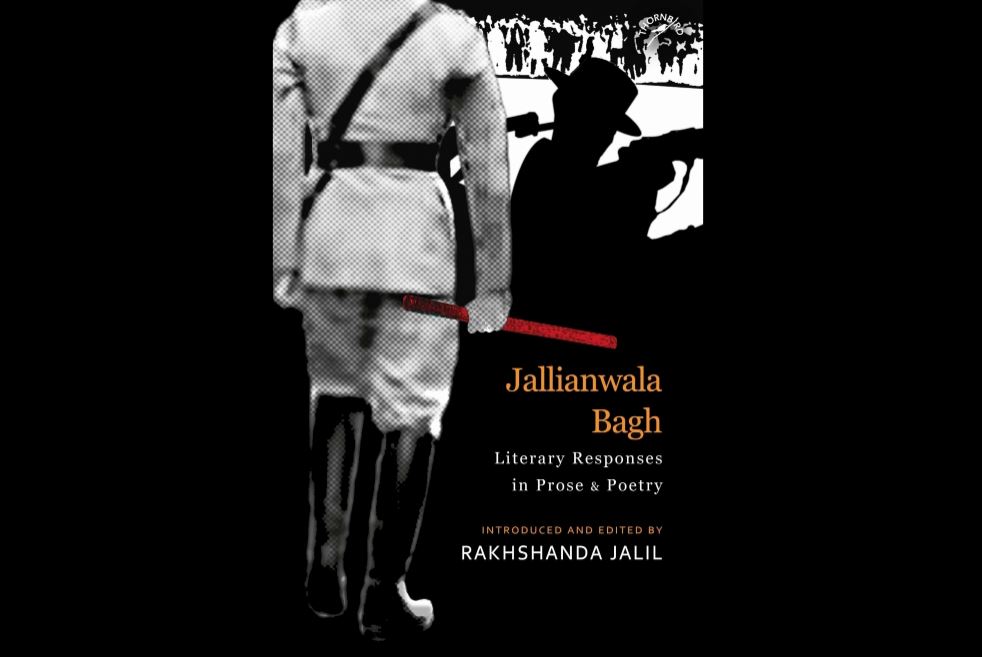

“I was curious to see how an incident that stirred the conscience of millions, one that had far-reaching implications for the national freedom struggle, that made British colonial interests in India morally untenable, found its way through pen and paper to reach the nooks and cranies of popular imagination filtered through the mind of the creative writer,” Jalil writes in the extensive introduction to “Jallainwala Bagh – Literary Responses in Prose and Poetry” (Niyogi Books/pp 227).

The book, she says, subjective as all such collections are by their very nature, “makes no pretence at being either exhaustive ot definite; it’s only claim is to open a window into the world of possibilities that literature offers to reflect, interpret and occasionally analyse events of momentous historical import. At best, the prose and poetry included in this selection offers ways of ‘seeing’ history,” Jalil says.

As is Jalil’s wont, she is being much too modest. Where else, in one volume, will you come across the works of Saadat Hasan Manto, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Mulk Raj Anand, Bhisham Sahani, Stanley Wolpert, Saojini Naidu, Muhammad Iqbal and Josh Mahilabadi, to name just a few of those featured.

What clearly comes out is the pain and anguish the Jallianwala Bagh massacre caused them and the burden of living under a brutal colonial ruler for whom justice and mercy didn’t exist. And yet, the fire of freedom didn’t die – indeed it was only reinforced.

Sample this from “Inquilab” by Abbas, about two friends, Anwar and Ratan, caught in the malestorm of the massacre: “A child was trying to wake up his mother who would be asleep forever; a boy of Anwar’s own age lay flat and lifeless. Everywhere there was blood. Anwar’s head reeled, his bowels contracted within him, he wanted to vomit but could not. He laid his head on the ground and saw the sky revolving and the stars dancing, a dance of death, and the crooked palm tree was dancing too. But before he yielded to unconsciousness, Anwar saw a glimpse of Ratan’s face. It bore nor trace of sorrow or grief but a far-way look, he was biting his lip to choke his sobs, and his eyes were ablaze with the cold fury of revenge.”

Then, there’s “Panjab 1919” by Sarojini Naidu: “How shall our love console thee, or assuage/Thy helpless woe; how shall our grief requite/The hearts that scourge thee and the hands that smite/Thy beauty with their rods of bitter rage?

Lo! Let our sorrows be they battle-gage/To wreck the terror of the tyrant’s might/Who mocks with ribald wrath they tragic plight/And stains with shame they radiant heritage!

O beautiful! O broken and betrayed!/O mournful queen!/O martyred Draupadi!/Endure thou still, unconquered, undismayed!/The sacred rivers of thy stricken blood/Shall prove the five-fold stream of Freedom’s flood/To guard the watch-towers of our Liberty.”

Jalil’s work will ensure that the flame that Jallianwalla Bagh lit will never be ensured.